Appendix IX

The Rhetorical University

"Action is with the scholar subordinate, but it is essential. Without it, he is not yet man. Without it, thought can never ripen into truth. Whilst the world hangs before the eye as a cloud of beauty, we cannot even see its beauty. Inaction is cowardice, but there can be no scholar without the heroic mind. The preamble of thought, the transition through which it passes from the unconscious to the conscious, is action. Only so much do I know, as I have lived. Instantly we know whose words are loaded with life, and whose not [1]."

Ralph Waldo Emerson, "The American Scholar", 1837

Internal Determinants of Science Courses within Communication and Writing Curricula

This is an appendix to the studies "Science Communication & Writing Curricula at Select Universities [2]" and "Web Development in Communication and Writing Curricula, [3]" which analyze the current state and evolutionary direction of two areas of interest to university departments of communication and writing. Both of these studies explore the roles of what Schummer calls cognitive and social aspects of a discipline [4]. Specifically, they pursue evidence as to whether communicating or writing about science are established elements in curricula from select departments, and similarly, whether courses in web development technology are a significant part of communication or writing curricula.

Both studies assume that curricular survey data (i.e., a study of course titles and descriptions as they appear on the web) are useful in revealing current cognitive aspects of contemporary curricula.

The challenge for science in communication and writing departments is largely one of cognition, answering questions such as What is it about the rhetoric of science that would cause us to pay any special attention to scientific discourse? or How are anti-science rhetorics able to persuade large segments of the public to adopt and act on non-science? The fate of science as subject matter in communication and writing programs depends on whether those who construct programs value science knowledge and methods or see any utility in science topics for communication or writing pedagogy. In short, the evolution of science communication and writing hinges on whether departments come to see science as something we do; the converse applies to science discourse communities which ask Is communicating beyond the discourse community something we do?

Schummer (ibid.) also maintains that in matters of cross-disciplinary interactions (e.g., where science meets communication or writing), social aspects are also critical. Academic departments are social units, governed by a sense of commitment to community, a commitment which "includes active engagement in increasing and improving the disciplinary body of knowledge through research, in communicating it through publications and in teaching it to students." Should a department collectively decide that cognitive aspects of science communication or writing are central to the knowledge, methods, and values of the department, a curriculum (and research agenda) may have the necessary support to prosper and grow. Schummer cautions that the opposite may occur: if a program has a mutually shared perception of boundaries of knowledge, methods, and values that does not include science as an object of study, science communication or writing may never thrive or may go locally extinct. "The commitment to the community reinforces the cognitive issues and, because groups tend to stick together, it reduces the experience of cross-disciplinary communication."

Schummer's view acts strongly on local perspective. We is experienced most directly as the local department or containing unit; a strong dean or provost may have considerable (albeit temporary) influence on programmatic perception of "what we do." Less directly, we is also experienced as being a member of a professional society or guild (e.g., NCA). Should a national professional society develop an interest group and a durable spot at annual meetings for science communication or journalism, the effect is in part to expand the scope of what is now considered part of the cognitive sphere of the discipline, the knowledge, methods, and values that may serve to legitimize movement into new areas within local departments. Again, the future of science communication remains largely academic and intramural, however.

External Social Influences on Science Communication and Writing

There may be a larger societal context at work in the twenty-first century that deserves broad consideration throughout modern universities. For at least two centuries, circumstances have favored planetary growth of the human population, with concomitant exponential growth in per capita material consumption for much of the world, resulting in increasing demands for globally finite resources (minerals and ores, fossil fuels) while placing enormous strains on earth's ecosystems (the atmosphere, oceans, and land). We are near or have already exceeded planetary carrying capacity, and the world of growth and material consumption that is all the developed nations have experienced within living memory must enter a period of retreat, controlled or otherwise. A brief sampling of a few of the products from the science discourse communities should serve to illustrate.

Of what has science made us aware?

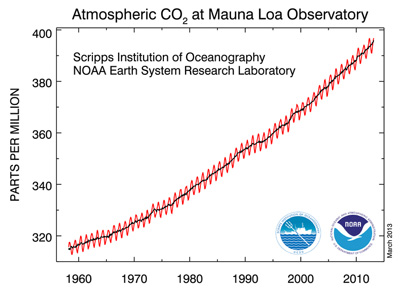

Science works through careful observation and shared reasoning toward a consensus on what we know [5]. The long series of observations from atop Mauna Loa volcano in Hawaii tells us that carbon dioxide in the atmosphere has increased steadily since we started recording in 1959. We exceeded 400ppm this year, up from ~280ppm at the beginning of the industrial revolution (mid 1800s). [6]

"Warming of the climate system is unequivocal, as is now evident from observations of increases in global average air and ocean temperatures, widespread melting of snow and ice, and rising global average sea level" [7].

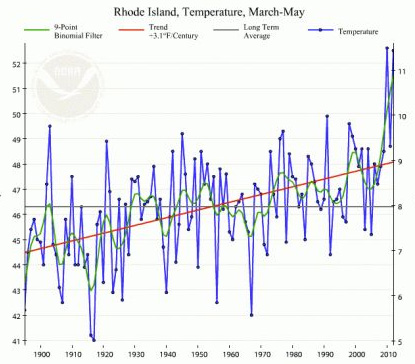

Climate change manifests itself everywhere: here, as an increase in RI spring temperatures [8].

Local climate effects are subtle, experienced as untrusted memories of a cooler planet in our youth. Equally distant and abstract, reports of steadily disappearing polar ice caps seem to have no meaning in busy day-to-day scurrying.

Still, it melts [9].

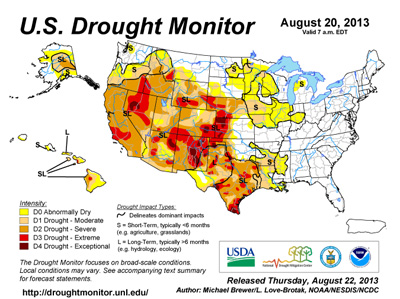

The impact of persistent drought—now drying up much of the nation's water and threatening food production—scarcely registers on the public mind.

Regardless, the heartland bakes [10].

The warnings of great scientists—public action is urgent!—fall on a deaf public ear. If the message is too dire for individual psyches, is it also too much for the collective great institutions of government? Are we unable to accept and act on the understandings of our best scientists?

In our paralysis, the need for action nevertheless persists.

It matters that carbons emitted by us—today—will have lasting, severe effects on the planet far, far into the future.

Still, we do not act.

"Since the dangers posed by global warming aren't tangible, immediate, or visible in the course of day-to-day life, however awesome they appear, many will sit on their hands and do nothing of a concrete nature about them. Yet waiting until they become visible and acute before being stirred to serious action will, by definition, be too late." [13]

"Since the dangers posed by global warming aren't tangible, immediate, or visible in the course of day-to-day life, however awesome they appear, many will sit on their hands and do nothing of a concrete nature about them. Yet waiting until they become visible and acute before being stirred to serious action will, by definition, be too late." [13]Sociologist Giddens helps us understand our political paralysis, but that understanding serves us poorly if we take it not as analysis of the problem, but rather as prediction of future behavior. Sitting on our hands leads to catastrophe: we have no alternative but to act—the sooner the better.

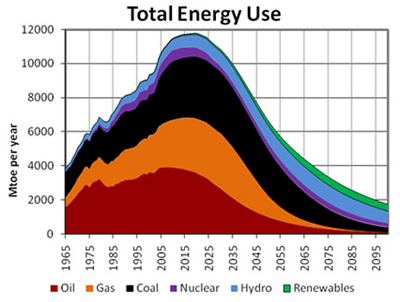

Not grasping climate change, we also are blind to our energy future. Last century, we lived the upside of abundant global fossil fuels—the era of the automobile and suburbs. Today, we plummet down the other side of the curves with a steadily accelerating, lethal fervor, oblivious to how we will all throw up as the ride ends [14].

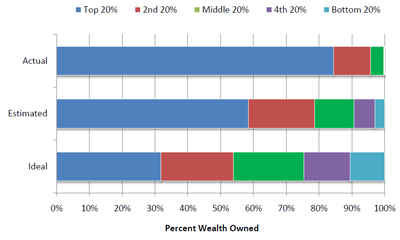

Critical public awareness is wrongly influenced by a growing gap in the distribution of wealth; under Citizen's United, control of politics and the media is tragically proportionate to wealth. Those who profit from keeping energy and greenhouse gas emissions as they are have delayed and distorted awareness, stalling the formation of the social movements we need to prepare for our future [15].

It should not be difficult to educate the current generation about what they must know of their own future. If you would like to read more about any of the above, these notes contain an outline and many references: [16]

From Awareness to Social Movement to Planetary Action:

The Persuasive Influence of Communication and Writing

There are egregious distances between what science teaches us (of what should we be aware?), our preparations for pending danger (for what should we plan?), and our public response to the great challenges of our lifetimes (how should we act?). Scientists are making us aware, and engineers are telling us how to prepare. But is higher education doing anything to translate awareness and technology into a vital global social movement?

An abundance of public polling data strongly suggest that far too many U.S. citizens and their elected representatives are dismally unaware of the precarious state of their planet and the unprecedented challenges to be faced by today's younger generations. Worse, too many people are willfully ignorant, incapable of making individual or collective decisions to cope with their own futures. A recently emerging plutocracy also contributed to rampant denialism, preventing coordinated adaptations to climate change and the end of the fossil fuel era (and with it the end of automobiles, suburbs, and agriculture as we know it. In short, evidence is strong that there has been a colossal failure to educate the public. Can higher education change that, and if so, is there a special role to be played by communication and writing disciplines?

Can Higher Education be Transformed?

The history of American Higher Education shows the great adaptability of our system.

- The First 200 Years: Educating a Leadership Class. From the earliest colonial colleges until after the Revolution, higher education was largely reserved for a privileged white, male social class ("Cultured Ornaments of Society")—a leadership caste of lawyers, physicians, and preachers, a life of classics, focused on the needs of the upper classes. [17] [18]

- Post Civil War: Improving Mechanics and Farmers. The scientific and technical needs of a rapidly industrializing nation led to creation of the Land Grant Colleges and Universities, created by the Morrill Act of July 2, 1862. The act set aside federal lands within each state (or equivalent land in western territories) to be used or sold to establish peoples colleges for education in agriculture and the mechanical arts (engineering), bolstering the rapidly expanding agricultural and industrial productivity of the nation. The creation of Johns Hopkins as the Nation's first institution dedicated to research and graduate education, in 1876, was accompanied by federal stimulus for research in the land grants, marked by passage of the Hatch Act of 1887. Extending the benefits of practical research findings to the Nation's farmers and industries was accelerated by the federal Smith-Lever Act (1914). Thus, the tripart land grant mission of teaching, research, and technical extension set the philosophical direction for the Nation's public universities early in the twentieth century[19].

- Early 20th Century: Industry Bolstered by University Science and Technology. Although the active pursuit of science was barely recognized as a proper part of higher education at the beginning of the 19th century, by the late 1800s science was ubiquitous. Flourishing research programs arose independent of the classroom, becoming vital to the missions of leading universities. The growth of the research universities in the first half of the 20th century followed an array of individualistic pathways [20]. Geiger pays particular attention to the evolution of research as an integral part of 16 leading institutions: California, Caltech, Chicago, Columbia, Cornell, Harvard, Illinois, Johns Hopkins, Michigan, Minnesota, MIT, Pennsylvania, Princeton, Stanford, Wisconsin, and Yale. "These sixteen institutions tended to head any list of quantitative indicators of university research—number of PhD.s produced, volumes in the library, or dollars expended for research. More importantly, they led all others in the quality of their faculties as judged by their academic peers [21]."

- Mid-20th Century: Dawn of the Multiversity. The mid-century growth of higher education was spurred by realization that the universities had previously-unexploited industrial and economic potential, demonstrated initially through their impact on the military-industrial state. The twin threads of the research university (following the Johns Hopkins model) and the technologically engaged state universities (the Land Grants) began to entwine in mid century [22].

- Late 20th Century: Reaching Limits to Growth. By the early 1970s, American universities had reached what may in retrospect have been their zenith. Campus life was diverse, robust, exciting, and virtually limitless in its possibilities. In the society surrounding and undergirding the universities, the middle class was also at a high point. Idealism abounded. The shared wealth was widely thought to be intrinsically rooted in the public value that universities were returning for the tax dollars invested by the public, an educational symbiosis largely of and for the middle class [23].

As state and federal budgets for higher education began to stagnate in the 1970s and to plummet for the next 40 years, the grim realities of the educational marketplace sent universities scrambling, shifting resources to high-enrollment programs, cutting low enrollment elements regardless of cultural value, in search of tuition dollars. Social amenities entered into the competitive mix as campuses competed as pleasant places to live for 4-5 years. Sports budgets stayed high in efforts to acquire prestige through winning programs. Research programs were hyped as "engines of economic development," although few campuses actually recovered the full costs of conducting research [24].

Higher education adapts to the broad needs of the society that sustains it. Its primary purposes have shifted from a role of maintaining a social elite leadership class, to building the agricultural and manufacturing underpinnings of a growing giant, to augmenting the national economy through invention and technological transfer.

Today, there is a new national need and it may be time for higher education to again transform itself. To address the needs for curtailment of the growth of the human population and its ecological footprint, a new cultural awareness is needed in the citizenry. This means a great change in attitudes toward consumption, human reproduction, and planetary stewardship, in turn requiring the emergence of a new culture of inter-generational and trans-national moral responsibility.

The teaching, research, and technical outreach functions of the modern university are still needed. What is new, however, is the need for more effective persuasion of not only the leadership class but of all citizens to undertake widespread reform. From what science has made us aware, the universities must lead in creation of social movements aimed at planetary transition.

There is a widespread perception among university faculty that to engage in the creation of social movements, or any active advocacy aimed at creating social movements, is somehow anathema to a principle of scholarly detachment. "The only way to do the type of science that I do is keeping your science separate from your personal political opinions. The distinction between what you know and what you believe is so important. Our value to society as scientists is preserved by keeping those two things separate [25]."

Certainly, the confusion of science with ideology undermines science itself. Abuse of science for purposes of theology, greed, or politics serves no useful end. And humans need to always be mindful of how easily we mix intellect with emotion, ideas with feelings. Science attempts to maintain a patina of objectivity, in method, language, and disposition. But to develop a cult of social disengagement, erecting walls between the laboratory work of science and the knowledge needs of the public also serves no useful end.

The challenges facing humankind as denizens and stewards of earth in the 21st century demand society's full attention. Ecology is no elective matter, something we can choose to attend to or ignore at will. These are indeed fateful times, an era demanding full attention from the entire populace.

The present study of science communication and writing in university curricula suggests that there is an innate active awareness of the appropriateness of disciplinary attention within the communication discourse communities. Beyond cognitive aspects and a slowly growing social acceptance of science as an object of rhetorical study, the strength of planetary challenges in the current century impose an imperative for exploration of greater research and teaching on the role of science in persuasive discourse.

If the twenty-first century university is to truly turn to the great needs of our time, communication studies must take a lead in formation of a new, societally engaged persuasive role for higher education. We must lead in the transition to the Rhetorical University.

Footnotes

William R. L. Anderegg, et al. 2010. "Expert credibility in climate change" (pdf), PNAS July 6, 2010 vol. 107 no. 27, p. 12107-12109.